(For why I started this, and if you want to work through the whole thing, start here.)

I have a confession. I never completed my review of White Fragility the first time around. I got to this chapter and just stopped. I believe DiAngelo should also have stopped. Stopped herself from writing or including this chapter. I will explain.

In the first paragraph, she says, on page 131, “In my work, I consistently encounter these tears in their various forms, and many writers have already provided excellent critiques.” She provides an endnote which I thought might lead to links to these “many writers.” I provide her endnote as a footnote here.1

The footnote provides a link to an article by Stacey Patton, published in Dame, December 15, 2014, and titled, “White Women, Please Don’t Expect Me to Wipe Away Your Tears.”

If you follow that link and read that article, you may be left wondering if DiAngelo read the whole article or just the title. The article is not an excellent critique of white women’s tears. It is a very personal expression of her frustration with Facebook encounters she’s had with white women “crying in her inbox.” It hardly qualifies as “excellent critique.” The article is worth reading, but Stacey Patton’s frustration with Facebook comments is hardly unique. The subject is adjacent to this chapter of White Fragility. But Patton’s article is much more nuanced, and even hopeful. It’s hardly the ringing endorsement that DiAngelo makes it out to be. But read it for yourself.

Later DiAngelo notes that:

Whether intended or not, when a white woman cries over some aspect of racism, all the attention immediately goes to her… when they should be focused on ameliorating racism. p 134

This is followed by a quote from the above Stacey Patton and a second endnote to the same article. So, her comment about “many writers” refers to exactly one. I’m certain there are other articles. But she only references this one. Again, I think she just read the title of Patton’s article.

Later in this chapter DiAngelo cites the horrifying example of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy who in 1955 was accused by a white woman of flirting with her. Her husband and his half-brother found the boy, beat him to death, disfigured the body, and threw it in the river. They were acquitted by an all-white jury. DiAngelo states that they later admitted to the murder and that the woman recanted in 2007. This would seem to be an example of how a white woman’s ‘tears’ got a 14-year-old Black child murdered. She specifically says that: “The story of Emmett Till is just one example of… ‘When a white woman cries, a black man gets hurt.’” p 133

That this happened is a reality that forcefully makes a point about the use of tears to cause real physical harm to another. Or is it? This woman lied. I realize that cried and lied rhyme, but they are not synonyms. Still, this is an egregious violent act centered on race.

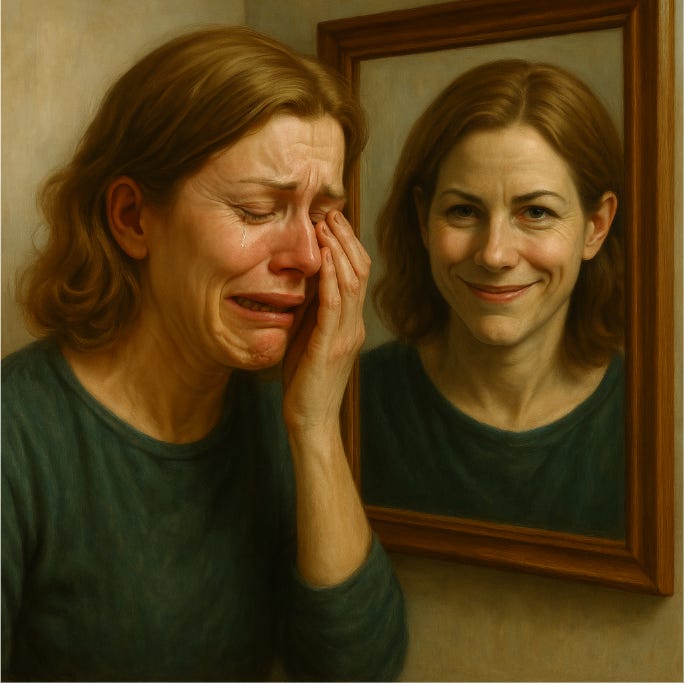

But that’s not her point. Her point is that white women who hear this story and are moved to tears do so not out of authentic care and concern, but rather are insensitive and manipulative racists.

OK, that’s a strong statement from me. And yes, it is my interpretation.

But, here is what she actually says in the very next paragraph:

Because of its seeming innocence, well-meaning white women crying in cross-racial interactions is one of the most pernicious enactments of white fragility. The reason we cry in these interactions vary. Perhaps we were given feedback on our racism. (Emphasis mine) p 133

Note, “seeming innocence” and “pernicious enactments.” Seeming innocence implies a look of innocence, not actual innocence. Pernicious enactments implies performative, i.e., white women cry as performance. She does not consider that perhaps these tears are tears of empathy.

One other assertion:

Not knowing or being sensitive to this history is another example of white centrality, individualism, and lack of racial humility. p 133

So, if a 20-year-old woman in 2025 learns of this story, hears about the torture and murder in all its grisly detail, and is moved to tears, this is her manipulating the conversation and basking in the protective glow of white fragility. To me, this is what DiAngelo is saying when she calls white women crying an act of seeming innocence and one of the most pernicious enactments of white fragility.

I reject that premise.

I’m not saying that it has never happened. I am saying that not every single display of emotion when learning of the effects of racism is a cynical and deliberate self-defense tactic used simply because all white people are fragile.

It seems clear to me that by this chapter, DiAngelo feels she has made her case beyond all reproach, and so she simply makes a number of sweeping assertions presented as demonstrated facts.

For example, this paragraph:

White men also get to authorize what constitutes pain and whose pain is legitimate. When white men come to the rescue of white women in cross-racial settings, patriarchy is reinforced as they play savior to our damsel in distress. By legitimating white women as the targets of harm, both white men and women accrue social capital. People of color are abandoned and left to bear witness as the resources meted out to white people actually increase—yet again—on their backs. p 136.

What do you do with that paragraph?

I mean this statement alone: “White men also get to authorize what constitutes pain and whose pain is legitimate.” Really? Says who? Is there a council, some sort of governing body? My ability to authorize what constitutes pain and whose pain is legitimate is news to me. Why am I just now finding out about my super powers?

And the resources meted out to white people increase, yet again, on the backs of minorities. On their backs. What does that mean? It’s a rhetorical device evoking hard labor. So, on the backs of black people resources are meted out to white people. That sentence sounds like it has meaning. But, truly, what is the meaning?

It’s a naked call-back to slavery. Rhetorically powerful, but does it track to white women’s tears? If I said anytime a German marries a Jew it is just a reenactment of the Holocaust, would you accept that?

By this chapter, DiAngelo has settled firmly in the premise that the society here in America is just simply racist. Although she defines racism in a manner that most people don't think of when they think “racist”, I feel there is some merit to her position. Any given culture is going to be ordered to the benefit of that culture. That’s kind of the point of a culture. So, a legitimate question is, what should a society do when injustice exists in the cultural norms? This is a serious and valid question and it deserves an answer.

DiAngelo may feel like she is addressing this question, but I don’t think she ever actually gets around to it. Why? I think her infatuation with the phrase ‘White Fragility’ derailed what could have been a serious argument.

This whole chapter is useless and demeaning and probably kept many, like myself, from reading her final chapter, which actually bears some fruit.

Next? “Where do we go from here.”

Previous | Next

For more book reviews: Books